Agriculture

In a sustainable civilization agricultural practices will be ecologically driven. Describing the pathway to such a civilization orients many of the current discussions, from soil health to new varietals to GMOs, and from scale (family farms to agribusiness) to questions of culture and local community. EcoCiv’s research focuses on dominant agricultural practices and alternative options, whether traditional or emerging based on new technologies. Clearly, agricultural practices are related to economic practices, energy sources, consumption and transportation, and ethical questions about practices and working conditions. High levels of consensus already exist in this field.

There are many organizations doing great work on transforming the agriculture sector. Below are a few examples:

Veterans to Farmers

Farming: Turning Protectors into Providers

Play the video for a short introduction

“My job used to be to take life, and now it’s to create life.” It’s hard to come back from Iraq and take a 9-5 job. But to put your hands in the soil and to make things grow — this is healing. Veterans to Farmers brings crops to life and people back to life. Many take what they’ve learned from organic farming and begin to teach others the same methods.

Read about these communities of veteran-farmers who are working the land, leaving war behind and cultivating their way toward ecological civilization.

An Interview with Richard Murphy, Program Director, Veterans to Farmers

A Bit of Background

- What is your mission statement?

-

- Mission Statement: The mission of Veterans to Farmers (VTF) is to provide access to education, experience, and training for veterans in the disciplines of urban and rural agriculture techniques. This includes hydroponics, aquaponics, traditional organic farming, homesteading skills, and business operations.

Vision Statement: The organization culture and curriculum allows for a decompression zone where veterans can assimilate effectively back into civilian life, creating potential for a well-suited livelihood through a permanent source of sustainable income, community, and contribution.

- Mission Statement: The mission of Veterans to Farmers (VTF) is to provide access to education, experience, and training for veterans in the disciplines of urban and rural agriculture techniques. This includes hydroponics, aquaponics, traditional organic farming, homesteading skills, and business operations.

- How long have you been in operation?

-

- Veterans to Farmers was founded in 2011 by Buck Adams, a U.S. Marine Corp. Veteran and the Executive Director of the organization. We became active as an organization in 2013 and started training in 2014. Currently in our second year, we have trained 80 veterans to date.

- Who are the key members of your team?

-

- I came on board as Program Director in 2014 as a volunteer and started teaching in 2015. I had been in contact with Veterans to Farmers since 2013, was looking to farm myself and was thrilled to find an unexpected opportunity.

- There are 2 other staff, soon to be 3. Joe and Daryl, both graduates, help train new veterans and are board members. We also have a few active volunteers.

- Do you have a board of directors/advisors?

-

- Yes, we have a great board, consisting of five members, including the two staff mentioned above. It is our first year actively working with them.

- What inspired the Founder, Buck Adams, to start this organization?

- In 2009, Buck, a social entrepreneur, recognized the business opportunity for growing food in the greenhouse industry in Colorado and established Circle Fresh Farms. Within 3 years, Circle Fresh Farms turned 12,000 square feet of greenhouse into 5 acres of greenhouse space for growing, becoming the largest organic greenhouse grower in Colorado.

- In 2011, Buck made it a personal and business initiative to train and hire fellow veterans. After successfully training 6 veterans, the word quickly got out about the program. With over 300 eager participants, Adams realized that the interest from veterans was much greater than he anticipated. He responded by developing a model/training program leading to business ownership and founding Veterans to Farmers.

- Greenhouse growing turned out to be very beneficial for the veteran community. Greenhouse farming is a very calming environment; it’s quiet, with running water, surrounded by living plants. It requires some of the same skills such as being willing to pay attention to detail on a very high level. And veterans are used to having physical on the job combined with classroom training. It’s a great fit for some of the veterans who were not going to fit well into normal 9 to 5 jobs.

- There is an opportunity in farming, and in other veteran-run programs to reduce the staggering number—22 veterans a day—who commit suicide.

- As one participant in the Veterans to Farmers program said, “My job used to be to take life, and now it’s to create life.”

A Look at Their Successes and Challenges

- What do you consider your biggest success?

- Testimonies from veterans about their experiences allow us to judge the impact we are having… and are a great driver of motivation for us. After training at Veterans to Farmers, our veterans have gone on to run a 100% solar indoor hydroponic farm in North Colorado; own a pecan farm in Texas; help run an upcoming Farmers Market; own a successful food truck company that sources local ingredients; be awarded a 6-month veteran internship for aquaponics in California; work full time for Denver Botanic Gardens; start a non-profit; receive the Future Organic Farmers Grant, awarded by University of Colorado at Denver (UCD), to continue studies in Sustainable Urban Agriculture; and enroll in a yearlong Marine engineering course to design floating farms.

-

- Our community relationships have been a huge success. It has really made us recognize that there is a civilian side to this that wants to help. In the beginning, we were very veteran-oriented and only had veterans on our board. We worked within the veteran community very thoroughly and were very plugged in there. Being able to start opening up to the civilian sector and have relationships with places like Denver Botanical Gardens where a group of civilians are training veterans for the first time. This exchange is opening up communication on both of our parts in a way that would otherwise not have been possible.

- What are the immediate and long-term goals you want to achieve?

- Immediate: We need to enhance our fundraising and grant efforts so that we can continue to operate, as well as pay stipends to the veterans participating in the programs.

- Long-term: I own 35 acres in Fort Collins with 24 raised bed gardens. Our goal is to turn this into a veteran homestead where we can train veterans in wheelchairs to farm and work with plants, etc. We have bees, chickens, hogs, etc. and want to use this as our training site for Northern CO and WY. We hope to get money for housing and to hire a Veteran Farm Manager.

- To continue to expand the training programs through partnerships with other local farms.

- What do you consider your biggest challenges?

- We are really good at what we do, teaching veterans to farm. Our biggest challenge is funding, to stay funded in a way that allows us to help veterans out in the way we want to. It is a challenge to keep the ball rolling and keep from burning out. We need to increase our grant writing capacity. If we could hire more people, we could “rotate ourselves out” for a bit.

- We need to create more support for out of state veterans. There is a huge demand but insufficient resources. One of our greatest needs is for temporary housing for out of state veterans while they are in training.

- How do people find out about your organization?

- People mostly have found us through web searches and social media outlets… We also have a newsletter that goes out quarterly.

- My first year I went to every veteran event in the state to get the word out about us.

- Food and farming are two subjects about which people in general are passionate, and there has been a great deal of interest among the veteran community. I was surprised recently to get a call from a guy in Korea who heard about us in a de-briefing.

- Where has your funding come from in the past?

- What other organizations do you partner with? Are there any others you would like to work with?

- Colorado State University. Through a USDA grant in partnership, they developed a very comprehensive curriculum for us that we use to teach veterans. We also offer all of our graduates a CSU certificate of completion into the programs.

- Denver Botanic Garden. DBG teaches the veterans organic, soil-based farming, along with small-scale community supported agriculture (CSA) classes. This is a 10-week course with both classroom and time in the field as well as food stands and deliveries.

- Rebel Farms – Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA). Basically growing in a greenhouse and hydroponics. This is a 8-week course , the veterans do hands-on and classroom work for 15 hours a week in the greenhouse– processing, harvesting, changing the nutrients and generally operating the greenhouse.

- Upstart University, an e-learning platform educating farmers of all growing styles to plan, build, and operate their own farms, is another optional component of the training program at Veterans to Farmers.

- Mental Health Center of Denver and Colorado Aquaponics. This is our newest partnership. Starting this October will be a 10 week course that will cover the CEA course as well as an introduction and hands on of the growing of fish with crops – Aquaponics.

- Other than financial, what type of support do you need?

- Help with spreading the word to let more veterans know about us.

- Like us on Facebook.

- We need volunteers to work on the website, newsletter, publicity, communications, grant writing, etc.

- Find any veteran cause about which you are passionate and support it

- Is there an organization that you particularly admire?

- Farmer-Veteran Coalition. We know the Founder, attend their conferences and think they are doing a great job supporting farmers and food leaders in the veteran community. Buck sits on a committee with him formed to lobby the government to make changes to the Farm Bill and GI Bill allowing for greater access to monies to veterans wanting to farm.

- If you had a direct line to top government offices (e.g., the president/governor/mayor/city council), what would you tell them?

- I would tell them to make sure they support small farmers, including veteran farmers; it is an expensive and risky proposition to buy land and equipment as a small farmer.

- The 2014 Farm Bill is not enough. Farmers need local and federal support. Put your money where your mouth is.

- Food is the number one thing that matters. We can’t rely on the food system the way it is. It is not a long term answer.

- Support the organizations trying to make the needed changes to our food system. Reach out a hand of support. Don’t just pay lip service.

- What does the term “Ecological Civilization” mean to you?

- What is your best piece of advice for other eco organizations?

- “Stay motivated and true to what you are doing. Take care of yourself in order to take care of other people.”

- “Don’t give up on your purpose yet allow change to naturally help shape the outcome. The universe never lets it happen just the way you expect. Muster down and believe in what you are doing and let it do its thing.”

Wrap-up Questions

- What have you learned from your work?

- “I got started in this work because I wanted the opportunity to train vets and work in the field with them. I am an Air Force Veteran myself and had my own issues. I found that it was a healing environment not only for them but also for me in a way I did not expect.”

- “We saw a need in our community that a pill was not going to fill. Twenty-two veterans commit suicide every day.” Clearly a different approach is needed. We see farming and other veteran-run programs as opportunities to reverse this reality and create a positive impact.

- What would you like the broader public to understand and appreciate from your experience so far?

- We are all in some way connected to this cause—on the food side (we all need food), the veteran side (we are veterans, family, friends and neighbors of veterans, etc.)

- The best way to help the cause is to support our local farmers. Shop at a farmer’s market! Support a CSA!

- If you have a skill set, whatever it is, volunteer to help.

- If you have a business, hire, train or support a veteran looking for a renewed sense of purpose.

Press Release (PDF)

EcoCity Farms

The Transition to Urban Farming — Growing and Educating Together

Play the video for a short introduction

In academic circles, theory tends to be exalted, while action is often undervalued. The gap between the two is often insurmountable. At the same time, many social justice activists have little patience with theoretical speculation, contemplation or reflection. For seasoned scholar/activist, Margaret Morgan-Hubbard, formerly an associate director of the democracy collaborative at the University of Maryland, praxis is a creative and generative process, involving interpretation, understanding and application in equal measure. It makes sense that she shaped a team that transformed a series of community-building projects into an ecological civilization that has intellectual rigor, community-centric planning, and a cross-section of sustainable values at its core.

Morgan-Hubbard applied years of lessons learned from her work at EPA, in national and local environmental and community organizations, and within the Academy, to the needs of her local community, and in the process has taken on the multifaceted challenge of building an ecological civilization: addressing food justice, crafting healthy food legislation and revising zoning ordinances, reintroducing old and co-creating new food traditions, introducing community nutrition and herbalism, developing farmer training protocols and emphasizing climate-smart environmental education – even cooking classes. “We have to create the future we desire– we can’t just sit around and wait for it to come!” she explains. “ECO is an on the ground, real world think tank,” says Morgan-Hubbard. She stresses that every one of us has to be a thinker and a doer, integrating mind and body. “Divisions between the intellectual class and working class simply cannot exist if we wish to sustainably reclaim our environment and our humanity.”

So the term “ecological civilization” is well earned. It’s also hard-fought, and the interview below tells an important story of successes, challenges, and needs for the future. Like other Eco Lab leaders, Morgan-Hubbard has wisdom, experience and cautionary tales for those of us who know an ecological civilization is the only future worth having. Will it be a challenging transition? Read on. Is it worth the fight? Eco City Farms has some practical answers.

An Interview with Margaret Morgan-Hubbard, CEO, and Viviana Lindo, Director of Community Education

A Bit of Background

- What is your mission statement?

- ECO City Farms serves as a prototype for sustainable local farming. Our motto is: “We grow great food, farms and farmers.” We work to change the existing food system that makes healthy fresh food a luxury available only to affluent communities. We teach vulnerable populations—children, youth, single heads of households, new immigrants and seniors—how to take charge of their consumption, habits and health to better secure their futures—through eating healthy, developing skills and pursuing career opportunities in the emerging healthy food system.

- ECO City Farms serves as a prototype for sustainable local farming. Our motto is: “We grow great food, farms and farmers.” We work to change the existing food system that makes healthy fresh food a luxury available only to affluent communities. We teach vulnerable populations—children, youth, single heads of households, new immigrants and seniors—how to take charge of their consumption, habits and health to better secure their futures—through eating healthy, developing skills and pursuing career opportunities in the emerging healthy food system.

- How long have you been in operation?

- ECO City Farms (ECO) was established in 2010 to serve residents of Prince George’s County, particularly the Port Towns.

- Who are the key members of your team?

- Our team consists of 9 staff (7 full-time, 2 part-time), 8 apprentices, dozens of volunteers and a yearly fellow from overseas. Everyone on our staff began as an apprentice or intern, meaning they worked without compensation for at least six months. Through this process, we got to listen, learn and grow with one another. ECO is an enterprise we are all in together. In addition to founder and CEO, Morgan-Hubbard, ECO’s staff includes Benny Erez, ECO’s senior technical advisor who was raised on a kibbutz in Israel; Viviana Lindo, ECO’s Community Educator who was born in Peru and earned her Master’s Degree in Global Studies at University of Freiburg (Germany), KwaZulu-Natal University (South Africa) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (India). Amanda West, ECO’s Operations Director who spent her childhood summers on a family farm in West Virginia and worked on Historic Preservation and Disaster Relief before coming to ECO; Fred James who is a legacy farmer from Alabama; Kayla Agonoy, Communications and Volunteer Coordinator, who returned to Prince George’s after earning her degree in Biology to give back to her community; Gabrielle Rovengo, Special Projects Coordinator who began her apprenticeship at ECO on her first day at college and graduated with a degree in soil science and a passion for food-related entrepreneurship; and Jacob Steelman, Farming Associate, is also a yoga instructor and seasoned public educator. Our newest addition is lead farmer, Aaron Griner, a multi-generational farmer and organic gardener from South Georgia, with wide range of farming knowledge and practice. Aaron worked on his family’s 350 acre farm for more than a dozen years, spent five years of working with two student-led gardening, education, and outreach organizations, and served for two years as an extension agent, educator, and community development worker with the Peace Corps/U.S.A.I.D in Togo before joining ECO in the Fall of 2016.

- Do you have a board of directors/advisors?

- Yes, ECO’s board is composed of 13 diverse and dedicated community members, including the CEO. ECO’s board serves as the eyes and ears of the organization, helping ECO to better connect to and interact with the community. While day-to-day decision-making is a staff function, the board is responsible for long-term strategic planning and fiscal oversight.

- What inspired you to start this organization?

- In my youth, I frequently visited the New Alchemy Institute on Cape Cod, a 12-acre former dairy farm that served as demonstration of “ecologically derived, human support systems – renewable energy, agriculture aquaculture, housing and landscapes – with minimal reliance on fossil fuels.” Although I did not consciously set out to reproduce their work, ECO is a beneficiary of their early experimentation in organic agriculture and ecological living. Throughout my career, I have sought opportunities to create projects and design systems that incorporate social justice and ecological praxis, and highlight the change I want to see in the world. As an employee at the University of Maryland from 2002 to 2010, I worked to find meaningful ways to engage the local community with the campus. I tried to address the fact that few of us in this County, other than students and faculty, truly connect with the university and the university has not been sufficiently relevant to the life of the community. Prince George’s County is 90% non-white. Many of the University’s neighbors are newcomers from Africa, the Caribbean and Central and South America. I was hired to make the university’s relationships with this community more small d- “democratic”. Toward that end, I developed strategic relationships with a number of local public schools from K to High School, helped found and staff a University/partnership community center, built the University’s (and County’s) first urban farm and community garden, and initiated a variety of inclusive, community-serving projects. I hired students and local residents to work at what became the “Engaged University.” Eventually, our activities took on a life of their own. We formed Engaged Community Offshoots, Inc., left the University, and launched ECO City Farms.

A Look at Their Successes and Challenges

- What do you consider your biggest successes?

- Over the past few years, we:

- Obtained five acres of land in two municipalities and built two “Certified Naturally Grown” urban farms in the Port Towns

- Produced and marketed hundreds of thousands of pounds of healthy food for our community

- Turned hundreds of thousands of tons of food waste into nutrient rich soil amendments with the help of millions of worms

- Provided life-skills education to hundreds of youth and families and with Prince George’s Community College certified more than 100 adults in Commercial Urban Agriculture

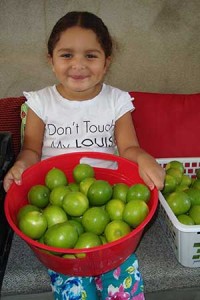

- Established and managed the Port Towns Farmers Mercado (PTFM) in Bladensburg, enabling area people to purchase locally grown healthy food in their community

- Inspired, initiated and passed legislation to enable urban farming and healthy eating in the County, engaging hundreds of residents in food justice advocacy

- Provided training and support for more than 22 Community Nutrition Educators, who as trusted leaders brought knowledge about healthy eating into familiar settings in local neighborhoods and trained hundreds of residents in nutrition and cooking

- Enabled 60 area children and youth to change their own and their family’s eating habits and awareness of where food comes from through 8 weeks of intensive enrichment activities

- Partnered with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance to train 40 skilled Master Composters in the theory and practice of community composting, who then enabled community gardeners throughout the DC metro area to create and/or access healthy soil

- Over the past few years, we:

-

-

- Enabled more than 30 aspiring farmers and/or food producers to move closer to their career objectives intensive experiential training at ECO City Farms

-

- What are your immediate and long-term goals?

- Our immediate goals are to complete a variety of construction projects at our farms to create better cold storage and learning spaces; expand our growing spaces and income-generating production to demonstrate the viability of urban farming; continue to nurture the Port Towns Farmer’s Mercado; work to diversify our support, particularly from small and major individual donors; continue to advocate for ecologically-sound and equitable policy change; train aspiring farmers and food entrepreneurs in all facets of urban food production, and build a school/community youth garden in Bladensburg.

- Our long-term goal is to create a just, vigorous and sustainable food system in the Chesapeake food shed with ample fertile soil, quality environments, livable incomes and decent working conditions for farmers and other food workers, and plentiful healthy affordable nutritious food for all.

- Our immediate goals are to complete a variety of construction projects at our farms to create better cold storage and learning spaces; expand our growing spaces and income-generating production to demonstrate the viability of urban farming; continue to nurture the Port Towns Farmer’s Mercado; work to diversify our support, particularly from small and major individual donors; continue to advocate for ecologically-sound and equitable policy change; train aspiring farmers and food entrepreneurs in all facets of urban food production, and build a school/community youth garden in Bladensburg.

- What do you consider your biggest immediate and long-term challenges?

- Securing and keeping County land in food production: It has been challenging to secure land to grow food in urban and peri-urban areas. The Planning Department would not allow us to build hoop houses on residential land. We had to take it to a higher level to get permission to build the vision we had for our first farm. In the end, we were given park land very near to the residential land we intended to buy. For our 2nd farm, we had to pursue a legislative remedy to overcome zoning restrictions to farming in multi-family communities. We now have two 15-year use agreements which enable us to farm on County and private land. But the fate of urban farming in our County is not yet secure. Zoning ordinance change is an iterative design process that takes patience and vigilance. We also seek an additional 10 to 15 acres of land and the tools and resources needed to launch an incubator farm in our County so that aspiring farmers who cannot afford to purchase or rent land on their own can grow needed healthy food. We are partnering with a private Quaker school in an adjacent County to enable some of our beginning farmers to cooperatively grow food for their own families, the school cafeteria, and the community on their land.

- Refining the Praxis of Restorative Farming and Adapting to Quickly Changing Climate and Urban Environmental Conditions: Urban farmers generally grow in raised beds. However, our practice as restorative permaculture farmers is to improve the soil and to allow nature to repair itself. We employ a variety of techniques to conserve water, sequester carbon, restore natural habitats, attract pollinators and encourage bio-diversity as we farm. At the same time, due to diminished natural habitats and constrained forests, more uninvited predators, insects and weed have become

problems on our land in recent years. And then there are the added effects of global warming. We are having to learn how to cope with erratic and unpredictable weather and rapid changes in the landscape as others try to cope as well. For example, two years ago, the Army Corps of Engineers added a few feet of soil to the berm next to our farm which dramatically altered air flow patterns, and this past winter, a unprecedentedly huge snowstorm ravished one of our hoop houses. And we have had to mitigate excess water and salt accumulations on our farm due to more frequent and heavy rainfall.

problems on our land in recent years. And then there are the added effects of global warming. We are having to learn how to cope with erratic and unpredictable weather and rapid changes in the landscape as others try to cope as well. For example, two years ago, the Army Corps of Engineers added a few feet of soil to the berm next to our farm which dramatically altered air flow patterns, and this past winter, a unprecedentedly huge snowstorm ravished one of our hoop houses. And we have had to mitigate excess water and salt accumulations on our farm due to more frequent and heavy rainfall.

- Training and Retaining the Next Generation of Farmers and Restoring Traditions/Creating New Habits that Value Healthy Food: In the longer-term, ECO faces challenges on the supply and demand sides of food access. In our community, gardening and cooking traditions have been lost and/or are seen as time prohibitive. Without reclaiming old traditions and installing new habits, training and installing new farmers and farms, creating affordable farm-shares and establishing new markets for greater healthy food access, while providing cooking classes and nutrition education, rampant diet-related epidemics in County communities will remain unchanged. Moreover, for healthy food to be affordable, food prices and ECO’s costs of production and education must be subsidized.

- How do people find out about your organization?

- People find out about us in many different ways. We regularly organize and participate in community outreach and public events in the Port Towns, throughout the County and in the DC and Baltimore metro areas. People hear about us through our work with and many visitors from local elementary schools, high schools, universities, and community centers and through our participation in conferences where we offer Community Nutrition and Herbalism workshops, Farm to the Table demonstrations, and guest speaker presentations. Another venue where people meet and learn about us is at the Riverdale and Port Towns Farmers Markets where we sell our food and explain our work. In addition, we send our monthly newsletters to hundreds of subscribers and maintain an ECO City Farms Facebook page, an educational website and of course, use word of mouth to get the word out!

- Where does your funding come from?

- Our funding is quite diverse for an organization of our size. We receive funding from Federal/State/City Government, Foundations, Major Donors and Small Contributors. Kaiser Permanente funded us early on as part of the Port Towns Community Health Partnership to aid low-income communities. We also rely on earned income.

- The 3- year Food Sovereignty Beginning Farmer Training grant we received from the USDA in 2016 builds on many elements we have already have in place. It enables us to integrate the courses we have been offering at PG Community College with our apprentice program, business courses, and master compost training to provide an year-long comprehensive work-skills development program for urban farmers.

- Our Saturday Port Towns Mercado was started with a USDA Famers Market Promotion grant.

- However, it is important to note that while funders are willing to invest in launching new ventures, they rarely invest adequately in maintaining or growing them. And they tend to quickly lose interest. Too often, it’s about funding novelty, not long-term needs. At the same time, in marked contrast to government, which is a self-perpetuating machine, non-profits are nimble, thrifty and rapidly deploy community-based solutions. However lack of sustained funding makes it hard for any of us to keep going.

- What other organizations do you work with?

- We accomplish all of our work through collaborations and partnerships, which are too numerous to mention. I will note just a few.

- A key member of the Port Towns Community Health Partnership, ECO City Farms works with four Port Towns and non-profits to increase community well-being. ECO has an enduring partnership with Maryland-National Capital Area Park and Planning Commission and the Autumn Woods Apartment Complex who provide land for two of our farms. For the Food Sovereignty training program, ECO partners with Prince George’s Community College, Maryland Organic Food and Farming Association, Blueberry Gardens, Sandy Spring Friends School, Prince George’s County Department of the Environment, and Montgomery College. For SEED2FEED, we collaborate with End Time Harvest Ministries, the Environmental and Natural Resources Academies at High Point and Fairmont Heights High Schools (PDF), and the Prince George’s County Youth Enrichment Program, Elizabeth Seton High School, Magic Johnson Community Empowerment Center, Whole Foods Market, and MOMs Organic Market. We also collaborate with the awesome chefs at Zenful Bites and the herbalist/nutritionist of Marble Gardens.

- We continue to partner with the University of Maryland Integrative Health Program to develop curricula and train community nutrition educators. We work with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance to move us toward an environmentally sound recycling economy and to offer the Neighborhood Soil Rebuilders program. We are on the Advisory Board of the Prince George’s County Department of the Environment who work closely with us on a variety of projects, and on the board of Future Harvest, CASA. Finally, we partner with International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) to host International Fellows. To date, we have worked with non-profit leaders Ghana, Macedonia and Malawi.

- Other than financial, what type of support do you need?

- When we first started, we resisted owning trucks and other major equipment, choosing instead to rely on the sharing economy. However, this is a very hard stance to maintain in this heavily consumerist society. As a result, we end up acquiring farm equipment, tools, supplies that occasionally fall into disrepair and require fixing. As our organization matures and expands in capacity, we also have greater equipment needs. So, number one need is better tools and farming equipment.

- We also have growing non-material needs, such as help developing a professional communications plan, to educate people about what we have created and accomplished.

- Most of all however, we need to engage in honest and open dialogue with peers about our problems and struggles so that we can learn from and support one another. People rarely admit that this work is really hard and that making money from small scale urban farming to sustain our efforts is especially challenging. We need know whether and how, in the longer term, producing locally grown healthy food can be sustained. I don’t mind suggesting that ecologically sound production needs to be subsidized. Big agriculture is heavily subsidized and is destroying our planet, but we are expected to be self-sustaining once grant money ends.

- What is your best piece of advice for other eco organizations?

- There are so many different challenges and obstacles that similar organizations and our allies will face as they swim against the tide — not Mother Nature’s tide — but the momentum and resources of large corporate and often government powers. My advice is to “never ever ever ever give up”, because what you are doing can and will change the course of history for the better. People need to see and experience positive change in order to gravitate to it. When you face challenges, find friends, partners, comrades, and mates to reclaim hope and keep going! The future generations of all species are depending on your perseverance and success.

- What have you learned from your work?

- On lesson is that what we are attempting is difficult and adversity is faced by all of us all the time. None of us are immune from it or somehow “entitled” to avoid it! Hope is a discipline we exercise whenever we create a vision of the world we want to live in, here and now.

- We are responsible for making the future. We can’t wait for it to come. The more we collaborate, the closer we get to what we want and need together. We are fortified by the energy we get from each other as we all struggle to live meaningful lives in harmony with nature and one another.

- Our vision is about changing the food system. As we work toward that end, we learn more about what that will actually take. At first, we thought it was just building a farm. What we ended up building was a more ecological civilization in the here and now and a social change organization requiring a much broader charge and capabilities. We learned that you can’t grow healthy food without restoring the environment, instilling habits of collaboration, teaching and learning what constitutes genuine community health: social, economic, physical, spiritual and environmental.

- What would you like the broader public to understand and appreciate from your experience so far?

- We want to make urban farming viable. And yet the cost of land and the cost of living is often prohibitive. Farmers don’t earn enough money to live in this area without subsidizing their production.

- We grow food locally where people eat it. People imagine that because there are reduced transportation and marketing costs, our vegetables should be cheaper. They don’t realize how many processed food costs are subsidized. People are always asking us for free vegetables, whereas they rarely request free pizza, cereal, soda or coffee. They do not understand how much hard work, time, effort, care and love is needed to grow even one delicious, nutrient-laden carrot!

- Healthy food is critical. Pills cannot substitute for food. And yet people don’t value vegetables like they value coffee or steak. They will pay more for a cup of coffee than a head of lettuce. We are a drug-oriented society, not a health-oriented society.

- To practice environmentalism means to first and foremost to do no harm. If you don’t know how an action or additive will impact us on the back end, don’t use it on the front end.

- Professors and teachers tend to think and teach that ideas are action. They generate brilliant concepts and share them with us. However, it is a huge leap to go from having a brilliant idea to actualizing it in the world. The action and reflection and learning involved in going from idea to action need to be valued and taught. They are, in fact, complicated and multifaceted, not unlike rocket science!

- ECO City Farms and other projects like ours are an “on the ground think tank”. We need to create an ethic where person values being both a thinker and a doer. Divisions between the intellectual class and working class cannot exist if we are to make our world whole and democratic.

Uncommon Good

An Ecological Civilization on the Ground in Claremont, California

Play the video for a short introduction

If you could hold a crystal ball in your hands and see the vision of an ecological civilization encapsulated in one place, it might look like Uncommon Good. Founder Nancy Minte’s holistic full-circle ecology includes a college mentoring program for underprivileged elementary, middle, and high school children, it manages over 50 plots of land that provide organic food – and employment – for the community, and it provides medical school debt relief for young doctors who tend to the very same families that are trying to lift their children out of poverty by sending them through the Uncommon Good education program. And this tiny earth-centered metropolis operates out of a beautiful, hand-made, solar-powered, mud-construction building tucked behind a Methodist church on a site originally occupied by Tongva Indians.

If you could hold a crystal ball in your hands and see the vision of an ecological civilization encapsulated in one place, it might look like Uncommon Good. Founder Nancy Minte’s holistic full-circle ecology includes a college mentoring program for underprivileged elementary, middle, and high school children, it manages over 50 plots of land that provide organic food – and employment – for the community, and it provides medical school debt relief for young doctors who tend to the very same families that are trying to lift their children out of poverty by sending them through the Uncommon Good education program. And this tiny earth-centered metropolis operates out of a beautiful, hand-made, solar-powered, mud-construction building tucked behind a Methodist church on a site originally occupied by Tongva Indians.

Nancy Minte has gotten her arms around the idea of an ecological civilization, and a visit to her website and a look at the interview below will provide insight, encouragement and healthy dose of optimism for the rest of us.

An Interview with Nancy Mintie, Executive Director, Uncommon Good

A Bit of Background

- What is your mission statement?

- The mission of Uncommon Good is to create a model for a society in which the basic human needs of all can be met in a healthy environment. To do this, it has established the following objectives:

- To break the intergenerational cycle of poverty through education.

- To help ensure access to quality healthcare for all.

- To feed the hungry and provide healthy food for the larger community.

- To create living wage jobs for the poor.

- To demonstrate how communities can build safe, comfortable, affordable and environmentally friendly homes and buildings for themselves.

- The mission of Uncommon Good is to create a model for a society in which the basic human needs of all can be met in a healthy environment. To do this, it has established the following objectives:

- What are your primary programs or services?

- How long have you been in operation?

- 16 years.

- Do you have a board of directors/advisors?

- Yes, we have a board with 20 members.

- What inspired you to start this organization?

- I wanted to help the poor and the planet.

- What did you do prior to starting Uncommon Good?

- I founded and directed the Inner City Law Center in Los Angeles.

A Look at Their Successes and Challenges

- What do you consider your biggest success?

- As our mission statement says, breaking the inter-generational cycle of poverty for the families that are moving through our programs – and so far we have sent over 100 kids from the depressed neighborhoods of the Pomona Valley on to college.

- What are the immediate goals you want to achieve?

- Finding the funding to keep the programs alive – we don’t have an endowment, so I have to raise the million-dollar budget from scratch every year.

- What are the long-term goals you want to achieve?

- I’d like us to be a mini-model of an ecological civilization – a closed energy loop – so that we keep renewing the environment for the next generation.

- What are the immediate goals you want to achieve?

- As our mission statement says, breaking the inter-generational cycle of poverty for the families that are moving through our programs – and so far we have sent over 100 kids from the depressed neighborhoods of the Pomona Valley on to college.

- What do you consider your biggest challenge?

- It’s always funding – there are lots of non-profits that rose up with the tech bubble, but in the crash the funding dried up. More entities are now trying to divide up the same lima bean, so to speak. We are a very holistic model, and most people don’t understand yet that we need an ecological civilization, where we address problems from multiple angles. People still think of a charity focused on a single issue – but the problem is bigger than that. There is more urgency, so the solutions need to be more dynamic.

- What is your most immediate challenge?

- It’s always the budget.

- What is your biggest long-term challenge?

- A lack of understanding at every level – government, foundations, and the individual donor community. They don’t understand the need to transcend the old models of what a non-profit should look like and how it should operate.

- What is your most immediate challenge?

- It’s always funding – there are lots of non-profits that rose up with the tech bubble, but in the crash the funding dried up. More entities are now trying to divide up the same lima bean, so to speak. We are a very holistic model, and most people don’t understand yet that we need an ecological civilization, where we address problems from multiple angles. People still think of a charity focused on a single issue – but the problem is bigger than that. There is more urgency, so the solutions need to be more dynamic.

- How do people find out about your organization?

- Word of mouth in the community – we are a living community, and people are clamoring to participate – they want the programs, but these are the same people who can’t support the programs. We also get some exposure from social media, from writing proposals, and speaking engagements.

- Where does your funding currently come from?

- Mostly private foundation grants – there aren’t many government grants for what we do.

- What other organizations do you work with?

- Local colleges, churches, school districts, the rotary club, chamber of commerce, and a wonderful and engaged retirement community called Pilgrim Place.

- What other organizations would you like to work with?

- The LA Food Policy Council, and of course more foundations – but you need a personal relationship to get foundation work started. Sending “cold-call” grant proposals is impossible – especially for places like the California Endowment, Packard Foundation, Irvine Foundation, Rockefeller…

- What other organizations would you like to work with?

- Local colleges, churches, school districts, the rotary club, chamber of commerce, and a wonderful and engaged retirement community called Pilgrim Place.

- Other than financial, what type of support do you need?

- “We always need more volunteers to mentor our kids. We need more tutors. And we need more people to come buy our vegetables. We also need more people of stature and means to serve on our board. Of course we also need a bigger, more consistent donor base.

- “We always need more volunteers to mentor our kids. We need more tutors. And we need more people to come buy our vegetables. We also need more people of stature and means to serve on our board. Of course we also need a bigger, more consistent donor base.

- Is there an organization that you particularly admire?

- This is not an organization, but Jill Stein is a voice of sanity and consciousness in the wasteland that is our political system. I also like Temple Beth Israel in Pomona – it’s very well run, very professional. The Claremont Presbyterian Church, and of course the Claremont United Methodist Church, who gave us the land to build on. There is also an organization called the Los Angeles Poverty Department – it’s a theatre group of homeless people – that started at the Inner City Law Center. They have given a voice to the most marginalized people in our country. And two of our participating doctors created Universal Community Health Center in LA. These are tremendous doctors with remarkable life stories – and they are about to open their second free health clinic.

- If you had a direct line to top government offices, what would you tell them?

- The president, governor, mayor

- Give some support money to the emerging non-profit models, not the big, hide-bound models that currently get all the funding. We also need educational debt relief for people who want to go into public service: doctors, ministers, teachers, legal aid lawyers, metal health specialists – students who have taken on huge debt to help society. I mean, how do you make the kind of sacrifices that non-profit work requires when you have so much debt? And we need help gluing together the best parts of the non-profit and for-profit model to create better community organizations.

- Your city council

- I’d ask for letters of support for my grant proposals.

- The president, governor, mayor

- What does the term “ecological civilization” mean to you?

- A closed loop energy system for everything from soil, to water, energy – everything needed for human life – like nature’s system is. And that includes a serious look at population growth – this planet can’t support unlimited growth. An ecological civilization also requires people who are educated as global citizens – not just to break the poverty cycle, but so that they can deal with the overarching problems of our age.

- What is your best piece of advice for other eco organizations?

- Our efforts will come to naught if there isn’t an evolution of consciousness – we have to bring higher consciousness to our own work.

The Big Picture

What have you learned from your work?

What have you learned from your work?

- It’s really true that love is the most powerful force in the universe – it’s just what I’ve learned from a lifetime of experience.

- What would you like the broader public to understand and appreciate from your experience so far?

- Creating an ecological civilization that ensures a just and happy life for every person is a work of great joy.